Much of Clear-Com’s success can be attributed to Butten, a colorful, crazy-uncle-type character with an incisive, sharp mind and an affinity for analog electronics.

Cohen, at the time a part owner of Family Dog Productions and lead mixer at the famed Avalon Ballroom, would become the front-man, the business leader of Clear-Com, serving as president from its founding through 1997. Butten, at the time the owner of Butten Sound, was the guy in the back shop who knew electronics and power and analog sound, both building and supplying speaker systems to the big bands of the day and working closely with the likes of Lindsey Buckingham on his blown-out guitar amps. This was the time of the Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead and the Doors. Concerts were becoming big business.

“In the early days a rock and roll concert might have a couple hundred people,” Butten recalls. “Next thing I know it becomes 5,000 people, and sending someone through the audience with a note to the stage is no longer feasible. It occurred fairly quickly. Bob and I asked ourselves, ‘What do we do?’ That’s when we began to experiment.”

The telephone-based communications in use at the time proved inadequate for high-SPL environments. The concept of a beltpack comm system was not new. Butten had spent a few months in Boston with Terry Hanley, who had developed a beltpack unit, with headset and boom mic, that would send signal to amplifiers in a back room and essentially serve as an attenuator for the earphone. The genius of the RS-100 that Butten and Cohen developed in that summer and fall of 1967 was that it carried audio and power over a shielded microphone cable and featured non-blocking, full-duplex audio signal flow. It also included the “Clear-Com Curve.”

“The first thing we had to do was to make it simple,” Butten says. “Plug this into that, put on your headphones, and it’s working. That was the hook. Everybody loved that. Then we had to dispel some old myths, the biggest being that you have to work in 300 to 3,000 cycles because that’s what Ma Bell had figured you could get away with on carrier channels. When we said that we go out to 8,000, everybody said, ‘What?’

“Well, we knew that the noise wasn’t going to go away,” he continues. “Bob bought one of the 1/3-octave graphic equalizers, and I used that to come up with the curve. What we found is that the intelligibility is all in the high end. You have the ‘s’ in sugar at about 3 kHz. Then you have the ‘sssss,’ which is about a 7kHz haystack. Those are very important for understanding speech. Then we had to tilt the response some to avoid the lower-end components from masking. You’re trying to convey that intelligence. You’re not trying to make them sound like Perry Como. You need that bright, sharp clarity to pop through the noise. The low end contains power, but very little intelligibility, and it tends to mask the upper frequencies. So there’s a hard highpass that cuts everything below 200 Hz.”

The result, in 1968, was the world’s first distributed amplifier intercom system, the RS-100 analog single-channel beltpack that became the foundation of the company and will still work with every product the company has put out since. At the NAB Show this month, the company will demonstrate a system incorporating 50 years of products, with a CS-200 2-channel throw down Clear-Com 2-wire Master Station with an RS-100 Beltpack into an LQ-2W2 2-wire network-connected box on into an Eclipse matrix via the brand new E-IPA Matrix network card. And it works.

The full history is well laid out on the company’s impressive website. Suffice to say it includes expansion into broadcast, theater and events, early advances into digital (1982), and various company owners, now happily settled in with Butten’s longtime friends at HME. The legacy is intact, the name has come to define a product category, like Kleenex or Xerox.

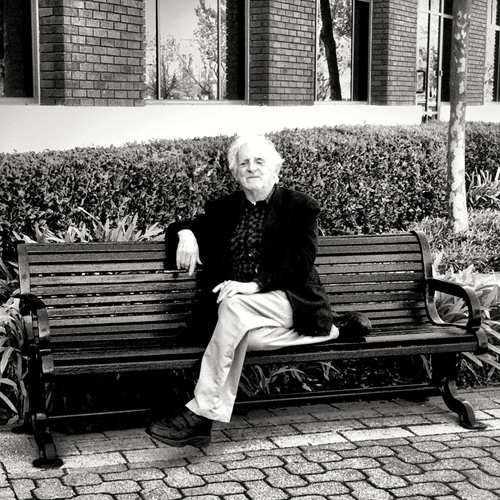

Much of that can be attributed to Butten, a colorful, crazy-uncle-type character with an incisive, sharp mind and an affinity for analog electronics. He drops in stories about the first Fender and Marshall amps and his time on stage helping out Carlos Santana, Eric Clapton (Cream days) and Herbie Hubert.

He laughs loud, sometimes at odd moments, and has an infectious love of life. He peppers conversations with his belief in the KISS philosophy, then offers his own version of the Six Ps: Proper Planning Prevents Piss-Poor Performance. At 72, he still goes to work every day, in a rumpled suit, sneakers and with a full head of disheveled hair.

Charlie Butten doesn’t always get the credit he deserves, for either Butten Sound or for his role with Bob Cohen in creating an industry, but he’s a damn fine man and he belongs on the Mount Rushmore of Live Sound. He really does.